Consistency patterns are contracts or guarantees that allow us to reason about what can happen in our distributed data systems, and how scrambled data can become.

A consistency pattern is considered stronger if it allows less possible histories, and usually makes it easier to build an application on top of it.

four high-level patterns

From a high level, we can define consistency in several general buckets. They are listed below in decreasing order of “strength”.

strong consistency

Strong consistency, also known as linearizability, ensures that any writes will always be seen by subsequent reads.

Info

This is difficult to achieve in distributed systems due to the tendency to use asynchronous-replication in order to maintain low latency in the system.

causal consistency

Causal consistency guarantees that rows that rely on each other will always appear in order for a user.

A common guarantee that is a superset of causal consistency is consistent prefix reads, which ensures that all replicas will receive updates in the same global ordering.

As such, this inconsistency can only become present in multi-leader or leaderless systems, as having a single leader accepting writes will always ensure that there is a single consistent global ordering of writes.

See this post on Educative for a diagram that demonstrates how version vectors can be used to implement causal consistency.

eventual consistency

A simplified consistency heuristic that states that all nodes in a system are guaranteed to reach a consistent state after an infinite amount of time.

An oversimplification?

Unfortunately, eventual consistency is not very useful in practice, as a system that becomes consistent after a long period of time (say, hours or days) is not useful for real-life applications.

In general, data or state that is updated asynchronously will have an eventual consistency guarantee. (See asynchronous vs. synchronous replication.)

Because of the vagueness of eventual consistency, several more specific guarantees can be defined.

- Read-your-writes consistency.

This form of consistency ensures that any writes made by a user are guaranteed to be read by the same user on subsequent reads.

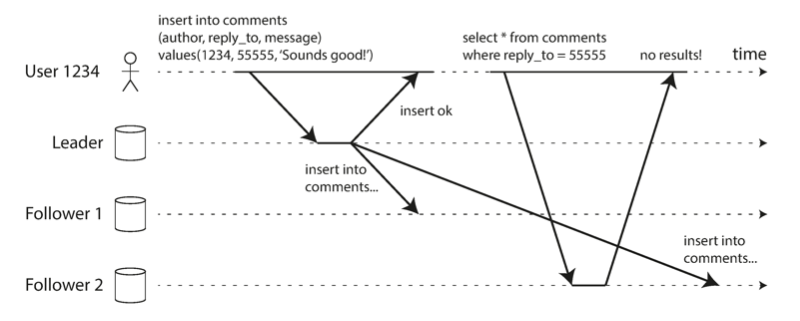

In the diagram below, we can see what happens when we don’t have read-your-writes consistency. The user in the diagram writes a comment to the leader, but then reads from a follower that hasn’t yet received the write yet.

It can be implemented in multiple ways:

- Ensure that a client reads from the leader node for a set amount of time after they submit a write.

- Ensure clients only ever read from followers that are synced within a certain time-delta with the leader.

- Ensure clients read all data that they have write-access on from the leader.

- Monotonic reads.

A monotonic read guarantee means that we ensure that the user never experiences backwards time travel (i.e. any subsequent ready query will always show a state that is the same or newer).

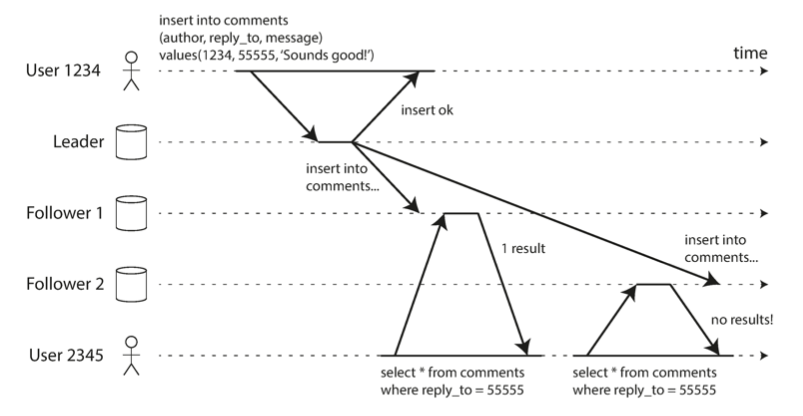

In the below diagram, the bottom user makes a read request and sees a comment, but then a subsequent comment is served by a replica that is more behind, leading to the comment “disappearing”.

The easiest way to avoid this is to have each user always read from a single replica. What happens when that replica fails is beyond the scope of this book.

weak consistency

The weakest consistency heuristic, which essentially doesn’t guarantee anything. This is useful in cases with temporal data such as phone calls or video calls, where we would rather drop frames than reduce throughput/availability.